Designers have an intuitive understanding of the evolution of aesthetic concepts, but many have not delved deeply into the philosophy behind them. With the rapid pace of design innovation, it’s easy to lose broader context, along with awareness of your own unspoken assumptions about design. That can be a problem — as in most cases, the philosophy behind the school of design is as important as what that design produces.

Designers who understand that are able to see what the precise intent behind a particular design philosophy is — which allows them to utilize it better. Skeuomorphism, for example, may seem outdated — but there was a reason it was used and understanding that can help you be a better designer.

Ignoring the philosophy behind design can lead to conventionalism. You start to make the same assumptions about what users want from UX design, how the flow should be structured, and how the different features of an app relate to each other. Your apps may get better in incremental ways as you refine your ideas and techniques (and as your developers add new features), but it becomes hard to do anything radically new.

Postmodern design can be an antidote for this stasis, helping you to examine your own assumptions critically, and come up with genuinely new solutions to problems in your products, your design process, and your approach to customers. Here’s what you should know.

What is Postmodernism?

Postmodernism is an intellectual movement beginning in the mid-twentieth century as a reaction to modernism, and it’s easiest to understand in that framework. In the late 19th and early 20th century, artists, writers, and intellectuals began to question the assumptions that underpin our society, from political ideas to architectural forms. This led to the start of modernism, and then later, postmodernism.

In art, modernism was associated with a whole range of movements, from impressionism to Dada, to Pop Art. Designers were empowered to question classical ideas of composition in a variety of ways, from experimenting with shape, texture, and negative space to incorporating an awareness of the viewer into the design.

Although modernism called many things into question, there were also certain assumptions it wasn’t able to critically examine. Modernists believed that art needed to progress to address a changing world, but they never actually considered that progress itself could be the problem — or that the need for progress was just an assumption supported by certain social, economic, and political systems.

They might have experimented with art, but they never really experimented with the idea of who the art was for — or why they were trying to put something “new” together in the first place.

That’s where postmodernism comes in.

Postmodernist theory rebels against modernism, by questioning metanarratives — which is a big word that essentially means the overarching stories and concepts we assume to be true.

A postmodernist would ask why they were being asked to make certain choices — whose perspective is being accounted for? Who is asking the question? Why is it being asked in the first place? They’d interrogate the very nature of the problem itself before even approaching the question.

Daniel Palmer, a Senior Lecturer in the Art History & Theory Program at Monash University elegantly summarizes postmodernism, using a wry answer given by one of his students:

”I once asked a group of my students if they knew what the term postmodernism meant: one replied that it’s when you put everything in quotation marks. It wasn’t such a bad answer, because concepts such as ‘reality,’ ‘truth’ and ‘humanity’ are invariably put under scrutiny by thinkers and ‘texts’ associated with postmodernism.

Postmodernism is often viewed as a culture of quotations.”

What is Postmodern Design?

It may seem like we’ve drifted far from mobile app design, but postmodern theory shapes our digital landscape. The ability to question fundamental assumptions has led to a profound self-awareness and an ironic and often playful approach to conventions.

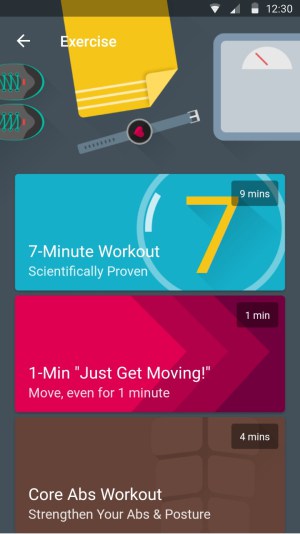

While the irony may not be as big a theme in mobile app design, the self-conscious awareness of narratives is a major factor in app design. Take The Fabulous App, one of our Best Mobile Apps of 2018. The app uses the metaphor of “A Fabulous Journey” to help users accomplish goals of personal change, such as getting in shape or improving your sleep habits.

The app focuses on developing successful rituals, using them to build up more complex habits. For example, if your goal is healthier eating, it might start by tasking you with drinking a glass of water when you wake up.

Being assigned all these tiny tasks all day long from your app could easily become tedious, discouraging users. So the app uses a material design style described as “mysterious yet familiar.” Aesthetically, it’s attractive but slightly alien in an intentional way, to preserve the feeling of a journey into the unknown.

That subverts the genre of the app — you’re not just working on self-improvement, you’re exploring the unknown. Users know that the app is doing something artificial, and they’re not really “exploring” anything, but it still helps them put themselves in the right headspace to accomplish meaningful changes.

Incorporating Postmodern Theory Into Your Mobile App Design

Postmodernism is more of a questioning attitude than a single set of ideas, and it would be a mistake to try to make a “postmodern app.” Rather, you should set out to examine your assumptions and the assumptions of your users, and look for opportunities to use those assumptions constructively in your app design.

One area where postmodernist theory has important implications is in UX design. Mobile UX depends heavily on visual and spatial metaphors, from desktops and buttons to gesture controls.

With skeuomorphism, the assumption was that the more realistic and immersive these metaphors were, the better they were for users. But as we developed powerful enough technology to display realistic textures and movement, and replace taps with gestures, designers began to question those assumptions.

Flat Design was in many ways a modernist experiment, attempting to update design with minimalistic forms specifically built for the digital world. Material design is where apps hit the postmodern age. It constantly eludes to the real world with shadows, layers, and internally consistent physics.

However, material design has developed its own ideology. There are codified ideas such as how colors affect user experience, how the flow should be optimized for productivity and comprehensibility, and how physics affects UX. It assumes the user is going to the app to get something done as easily and pleasantly as possible and has a whole set of beliefs on what could help users accomplish that goal.

Those beliefs might not be true for your users. A skeuomorphic design might be appealing for certain apps as a way to evoke nostalgia or create an immersive experience. Contrasting or even clashing styles could surprise and delight your users or draw attention to a particular feature. Novel or counterintuitive physics might give an app a pleasing novelty that’s fun for users to figure out.

Postmodernism can also apply to your own process and workflow. The tools you use impose soft constraints on the decisions you make as you build an app. Starting with a simple vector animation tool might lead you to privilege layout over texture, while moving straight to a more powerful tool like Adobe XD may lead you to emphasize the latter more.

If you start designing your app on your laptop, you might end up with a finished product that’s different from something you started on your desktop — or something you started by sketching it out in a notebook (or on a smartphone, or tablet, and so on). Likewise, new tools will change your perspective — especially as you begin to master them.

The limits of each platform will influence the problems you see — and how you try to solve them.

That relates back to the apps you build for users. Many apps and programs self-consciously pose constraints that users find creatively useful. One example is the program VCV Rack, an open source program emulating the workflow of an analog synthesizer with patch cables.

The app isn’t practical from a productivity standpoint. In a typical Digital Audio Workstation, composers can simulate virtually any instrument instantly, move some faders around and then jump right into arranging. In VCV Rack, they need to first build the instrument from simulated circuits. Just to make a note play, for example, a user would need to add an oscillator, run that oscillator’s single channel to an amplifier, then use a filter to control the timbre (and that’s a simplified explanation!).

However, users find it creatively valuable in part because of its constraints. They have to think of sound at a more granular level than just notes and harmonies, which can provide its own kind of creative freedom.

Understanding the role constraints play in the creative process might not help you build a more efficient app, but it could help you build a more compelling one.

Never Stop Experimenting

Postmodernism is a challenge as a philosophical concept, but it doesn’t have to be a challenge as a design concept. You already experiment with color, shape, and texture. Experimenting with your users’ perceptions — and your own — is just one more step you can take toward developing an app that’s more than just a tool.

Proto.io lets anyone build mobile app prototypes that feel real. No coding or design skills required. Bring your ideas to life quickly! Sign up for a free 15-day trial of Proto.io today and get started on your next mobile app design.

Have a favorite example of postmodern design? Let us know by tweeting us @Protoio!