Good design has always been part art, part science. Principles dictating proportion, shape, and layout go back to the ancient world — or at least the birth of the industrial age. As long as there have been buttons to push or levers to pull, designers have worked to balance attractive design and simplicity.

There has often been tension between these two elements, with expressive, ornamental design aesthetics battling a bare-bones, functional approach. But lately, art has taken a backseat to science in shaping the way the industry talks about user interface design. Simplicity, convenience, and the use of recognizable conventions have become the key principles behind what we call “good design.” Companies measure everything from user opinions to eye tracking and response time to distill design goals almost to mathematical formulas.

At the same time, designers are constantly told to delight and surprise users with their mobile UI — UI that’s supposed to be organized in the most familiar (and presumably least surprising) way possible. And they do just that.

There are still apps where pleasing physics, charming microinteractions, and clever innovations add up to something more than the sum of their parts. But to keep that magic alive, we need to remember that simplicity isn’t the only laudable design quality.

Creating Visual Interest by Rejecting Unwarranted Uniformity

Researchers have made remarkable strides in analyzing user behavior, but the meaning of their research is often lost in translation. Designers are often artificially constrained by a misunderstanding and misapplication of science.

Project managers and other decision-makers want to reduce risk and increase the usability of apps based on the latest research, but often lack the training to evaluate said research.

One classic example is design layout. There have been numerous theories and studies on how users scan pages. These studies are used to justify layout patterns — patterns that can supposedly make websites and apps more readable.

For example, the Gutenberg pattern is based on the idea that the user’s gaze traces a series of horizontal lines from the top right to the bottom left of a page. According to this theory, designers should place the most important elements along this axis, and leave less important ones on the top right or bottom left. Other patterns based on user research include the F-pattern, where the gaze traces an F shape, and the zig-zag pattern.

However, as Vanseo Design points out, these patterns are routinely treated as gospel in UI design situations where they’re irrelevant:

“While patterns like the Gutenberg diagram, the Z-pattern, and the F-pattern layout suggest that there is a natural path the eye will take through a design, the reality is they refer only to designs dominated by large blocks of text with little to no hierarchy.

If that describes your design then any of these three patterns might serve as a guide for where you’ll want to put your most important information.

As soon as you begin adding elements of varying visual weight, the path the eye will take through your design is the one you create. You can choose to reinforce Gutenberg, F, or Z-patterns if you want, but you aren’t limited by them.”

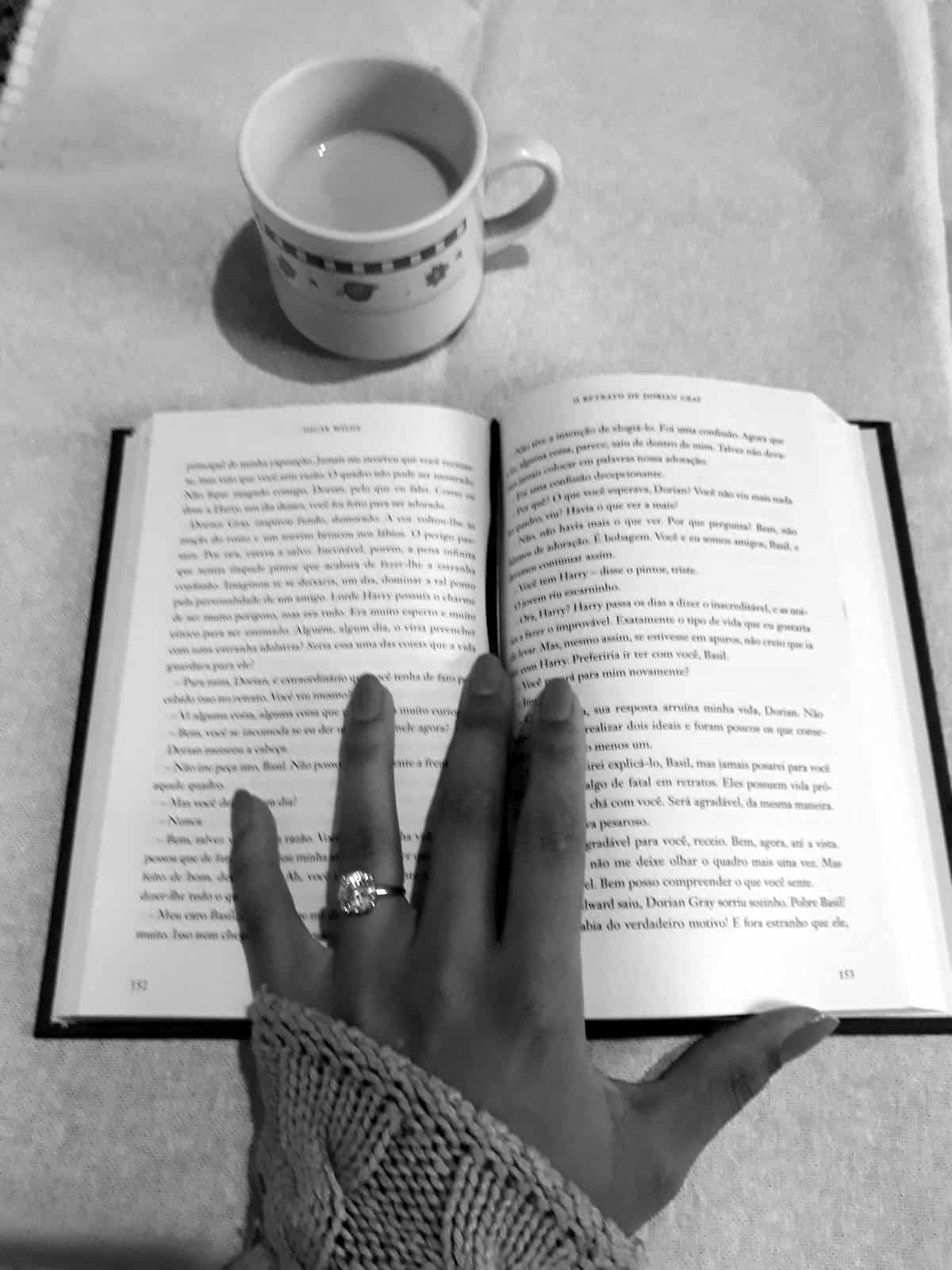

When mobile UI design is high quality, users are actually far more likely to focus on images and may ignore large blocks of text altogether. In a study of mobile commerce apps by Best Buy, Hyatt, and Pizza Pizza, researchers found images and prices were a major focus in each app — often to the exclusion of text.

In the Best Buy app, “participants didn’t read the product descriptions, even though they took up half of the screen real-estate.” Similarly, Hyatt users skipped hotel descriptions and “focused on the images and the prices.”

In other words, users don’t automatically follow a preset pattern, they follow the design choices you make. You still can draw on conventional design patterns for text-heavy screens where users need to focus on print, while making more unconventional design choices in other areas to increase visual interest. By understanding the science, you can use conventional patterns when they’re relevant and avoid being constrained by them when they’re not.

Enhancing UI Design Quality Through User Perception

Mobile designers might feel limited by the amount of screen real estate — so it’s important they understand the more important limit is user perception and cognition.

You can cram a lot of data into a modern 5 or 6-inch smartphone screen, but it quickly gets overwhelming to users. Even if every element is clearly designed, the UI quickly gets too cluttered with buttons and fields, degrading the UX.

Using different screens for different functions is an obvious part of the solution, but it’s only one part. The best mobile UI design uses the science of user perception to make the app more intuitive, immersive, and compelling.

Gestalt psychology provides a number of extremely useful tools for UI designers to support user cognition. Gestalt principles show the ways users associate objects into groups and make inferences about visual information, including:

- Proximity: When objects are close to each other, users are more likely to see them as connected. This is closely related to Common region, where objects in the same area are perceived as a group.

- Similarity: Giving objects similar colors, shapes, sizes or other features can signify a relationship.

- Symmetry: A symmetrical appearance or layout can show users that objects are part of a group.

- Common fate: Objects with the same orientation or direction of movement appear to be connected. For example, if you have six down arrows on a page and one up arrow, the down arrows will be more likely to look like a group.

- Closure: Groups of incomplete objects can be seen as a single recognizable object. This is often used in icons, where part of the image is created out of white space.

Gestalt principles are already an implicit part of how apps support basic goals of user interface design, such as ease of use. For example, in the Stitcher app, play, fast forward, and rewind controls are in one common area to make finding them easy.

Episodes are all identified with the same arrow icon. The app also conveys a second layer of meaning by reversing the color scheme and adding shading to apps the user has started, but not finished.

However, smart UI design goes beyond simply organizing information effectively on a screen, drawing on user cognition to create a coherent experience throughout the whole app. Common fate and other Gestalt principles can show the state of composite objects at a glance, and allow the user to infer the state of individual components without pouring through all the individual elements.

For example, in project management tasks an icon can tell you what phase a project is in, using shapes, colors, and other recognizable characteristics to give users information about the project components based on similarity to other projects.

And the applications don’t stop there. Gestalt principles can help you develop a coherent visual language to enhance immersion or improve branding. It can support storytelling and enhance engagement. It can even help with education by creating intuitive connections between different facts, elements, or lessons.

Using Memorable UI Design Features to Hook Users

A great first impression might not be enough to make an app successful, but it certainly makes the job easier. A distinctive flow or control scheme, attractive design or even a memorable splash screen can help you stick out from the crowd and earn more downloads — and hopefully, more dedicated users.

To make your app memorable, consider where potential users are going to see or interact with it and what features can make it stand out.

Often, this memorability is one of the main goals of user interface design. Many simple apps have gained a following through a novel or playful UI, designed to hook users in. For example, the appeal of Sonic Lighter by Smule was that users could control it just like a lighter — flicking the screen to light the flame, blowing it out and “lighting” other iPhones by touching them together. Users found that interface fun and engaging, and the app spread like (ahem) wildfire.

In other cases, designers can hook users through demos, which highlight something distinctive or exceptional about the interface — if the designer (and the demo) can make that feature clear to an audience seeing it for the first time.

Assembly, one of our favorite freelance designer apps, accomplishes this through its innovative use of vector graphics for highly mobile sketching and design. The app works with simple shapes, which can be rotated, scaled, and combined into complex shapes. Those complex objects can be treated in the same way as simpler shapes, which lets designers build very complex scenes on the go using touch alone.

Because the UI is very clearly designed and shows features like snap-to-grid, scaling, and shading explicitly, users can take in its full capabilities in a short trailer. In a crowded field of design apps, something like that makes it stand out for viewers.

Designing on the Cutting Edge

Good design should be simple, but never boring. By balancing conventions that help users and innovations that inspire them, you can keep building apps that advance your company, your career, and both the science and art of design. And once you get that design nailed down, make sure you make a functional prototype so your developers can build exactly what you’re looking for.

Proto.io lets anyone build mobile app prototypes that feel real. No coding or design skills required. Bring your ideas to life quickly! Sign up for a free 15-day trial of Proto.io today and get started on your next mobile app design.

What are your UI design goals? Let us know by tweeting us @Protoio!